Enzo Cucchi interview 1984

Click to enlarge…

Man Made Myth

Kay Roberts and John Coleman talk to Enzo Cucchi

At the time of Enzo Cucchi’s exhibitions in Anthony d’Offay Galleries 9 & 23 Dering Street

(taped conversation on Tues 15 May 1984 at Anthony d’Offay Gallery, 23 Dering Street, in the company of Mrs Cucchi & a representative of the gallery, who translated because Enzo Cucchi spoke in Italian)

Enzo Cucchi is the third of three artists dubbed in New York at the beginning of the decade “the three C’s” (Chia, Clemente and Cucchi), the best known, and the most successful, of the new generation of Italian painting. Cucchi comes from Ancona, in eastern Italy. This area, with its mixture of industry, landscape, rural, rural agriculture and the sea, infuses his work.

Cucchi chooses to mythicise these elements of his own existence and in doing so his art tries to make legendary the everyday, to mystify the familiar and to do simply things heroically.

In an age when photography would seek to embody truth, Cucchi’s art attempts revert the image to the status of the Myth: where its meaning is ambiguous, open to interpretation and impossible to assimilate.

Cucchi has just had a one man show of new paintings at the Anthony d’Offay Gallery.

(John Coleman)

EC: Ask me my weight

JC: I want to ask you if you go to see many films.

EC: Not many, but many boxing matches.

KR: Did you go to the Bruno-Smith match while you were here?

EC: English?

KR: There was a big match here on Sunday.

EC: We were just travelling – there was one, Sugar Ray Leonard.

KR: I wondered if you’ve seen that one because Bruno was winning for seven rounds but he was knocked out in the last round …. And If there was any equivalent in painting.

EC: Sure - & it’s not so rare, because both things are very similar, boxing & painting -because the same discipline is needed – the same moral sense, the same spiritual sense. Sugar Ray Leonard stopped boxing because he lacked the sacred fire inside and that’s possible in painting too.

JC: Wasn’t he just too rich?

EC: No, it’s a spiritual thing you have, or you don’t have – even if the world may think everything depends on money, but painting and boxing depend on this old story of some sacred fire inside yourself. |They say old Sugar Ray Robinson didn’t train at all, just danced all night before fighting & he was the biggest one of all centuries, naturally. He already was warm from the beginning because he had a sort of theatrical way of behaving from the start, because he wore seven robes, the seven different colours of the rainbow.

JC: Are painters like this, are painters equially theatrical?

EC: It may look theatrical but it’s much more, it’s something to do with the relationship he has with the universe.

KR: I read you’d said that ‘in this century prize fighters and prostitutes were the only spiritual people …. And prostitutes were the only spiritually represented people’. I didn’t understand this statement, that they are ‘the only moral restorers.

EC: Because they are free from the commonplace & they have a moral & spiritual sense that no one else has … of our modern day.

KR: Because it’s so black and white? Because they are faced with a certain reality most of us aren’t?

EC: They are the only witnesses left of our spiritual richness at this time. It has nothing to do with social reality or problems.

JC: But they are both physical in the extreme.

EC: Yes, but they take care of their bodies in a way that their soul must be cured. It’s not like mnormal people cure their bodies.

JC: Not like aerobics?

EC: That’s the pervasive symptom – that you just have the body ro be cured and nothing else, but that’s not the case with fighters and prostitutes.

JC: Do you feel your farmyard opera is an escape from the real? Do you see your painting, your kind of operatic ‘other world’ style as an escape from the mundane every day?

EC: It’s just the contrary, because painters, like boxers and prostitutes’ want to go on having a strong relationship with concrete things. This is the mystery of painting … a pear like the form of a pear …. So, aerobics or gymnastics are no mysteries left.

KR: Spirituality isn’t present in many lives and certainly not in GB – if you are born Italian have you got an unfair link into this world?

EC: Yes, Italian people still have a sort of cynical relationship with things, with everyday things, which is the only way they can stick to everyday things.

JC: Is it one job of the artist to reinvent myth?

EC: The task of the artist is to have a great energy of great invention and to bring back what is already made, what you already find in reality, there’s nothing new.

JC: And looking at the work that the audience should feel that power to reinvent themselves, that it inspires in that way, that people can change their lives.

EC: that’s the traditional problem of iconography which in the last 100 years the intellectuals tried to destroy.

JC: Do critics, commentators on art, get in the way of art, and do you think they block it?

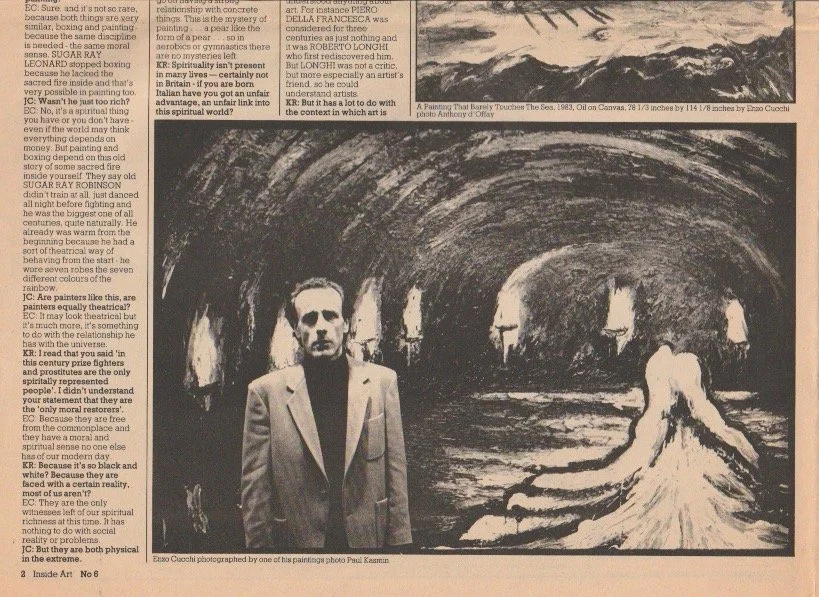

EC: Critics have only the function of blocking everything. They have never understood anything about art. For instance, Piero della Francesca was considered for three centuries just nothing, and it was Roberto Longhi, who first rediscovered him. And Longhi was not a critic but more especially an artist’s friend, so he could understand artists.

KR: But it has a lot to do with the context in which art is made. Piero made the little cells in Florence in the monastery, you go inside like the monk, and you appreciate the spirituality, but how can any of that be explained, apart from how you feel about it?

EC: You mean if Piero had freedom in making the work or not?

KR: No. That the experience is total and so it’s difficult to explain this feeling and that is the critic’s difficulty. And what people have lost is the confidence in saying they feel something and they therefore look to other people to tell them how they feel.

EC: Because for the last 100 years all the intellectual work was to destroy iconography. …… while all the world has always been stuck on images.

JC: Do you feel you mystify the familiar?

EC: Who mystifies?

JC: The artist in his work.

EC: What do you mean by mystify?

JC: To complicate the idea of seeing, that things aren’t as straight forward as they appear, to reinvent mystery.

EC: Now for instance, Masaccio, what he tried to do was to paint people as they actually stand – simply and familiarly standing, and that’s what everybody does. In the morning when you get up, you stand, you hope you can stand, that is something deeply familiar, and not so ….

KR: But the Masaccio’s I’ve seen are like a waking dream.

EC: If you look at Masaccio’s faces or bodies they are so natural and in every day positions …. Actually, his relationship is not with the people but with the universe. The first thing you think about is standing, it is what I do when I get up each day.

JC: So, the artist does celebrate or make legendary the everyday?

EC: Each artist does celebrate just one thing or two things he wants to talk about or celebrate.

KR: So, in a way does it become like a mantra?

EC: I don’t know ‘mantra’. That may be interesting but what I am interested in is just the Mediterranean Spirit, we shouldn’t mix up the west and the east.

JC: Is your work nationalistic?

EC: Not nationalistic in the historical sense, just national in the sense that I want to stand with my feet stuck on the ground – that in Italian means to be very concrete, very…

JC: On Italian ground?

EC: It is the only ground I know. Not like would be intellectuals who pretend to know everything.

JC: Are you doing an art you can’t help doing?

EC: Yes. I can also think of something else, but I can’t because of that obsession. I would prefer to go to the horse racing but I can’t because of this obsession.

KR: Whatever you did would it have to be an obsession, if it was horse racing … whatever one did it should be total?

EC: It should be like that - total.

JC: So do you feel that you are tapping into Latin / Mediterranean passion – a hot bloodedness?

EC: It the only sea I know.

JC: Why do you put real objects in your paintings?

EC: It’s simply a problem of light. I don’t care about objects or real objects, it’s just a problem of light, light is the only thing I know.

KR: They are both the representation of something, but one is a real representing and one is an illusional representation of something.

EC: Not quite representation, just presence. An appearance of something.

JC: It makes more mythical the subject matter.

EC: The problem is light, just a formal problem. For instance, many painters work with the sea as a presence not as a representation. I just feel the presence of the sea, I don’t represent the sea.

KR: In the same way it’s not actually necessary to actually see the sea but to feel the presence of the sea.

EC: And to feel like the fisherman who feels the sea and its danger.

KR: Then is it more to feel the sea than to see the sea?

EC: Sure.

JC: So your work is always going to fail, never quite to do justice to the power of the subject, never going to equal, trying to compete?

EC: Yes, I feel like the executioner. I would like to live in the house of the executioner. In Ancona there is an old executioner’s house on a hill.

KR: I once live in the house Fossoyeur’s house in a French village, the man who dug the graves and made the coffins. The house was named by that and definitely had a feeling about it.

EC: That is not definitively an executioner. An executioner may see the eyes of the man he is going to kill.

JC: Is the strangled chicken the voice of the dispossessed consumers of culture, or the animals – the pigs heads ….. could we see them as the dispossessed consumers – this distance from them, that they are repressed.

EC: The chickens are like lifting feelings into the air, the idea of lifting up in the air. Like the other idea I have of things going towards the sea. So everything goes towards the sea or towards the air. I think of ….(?) ….. when he said that all old men tend to go towards the sea, along the beach. Like they can’t help do otherwise.

JC: Do you think yiou belong to a tradition in painting?

EC: More than a tradition. What we call a continuous fact in time, a long time.

JC: So its not a kind of progress?

EC: Just the contrary. I just keep pace. Progress is just an idea without image. Just an aggressive problem.

KR: A false idea?

EC: Yes, becaue its just an idea of aggressive man over another man.

JC: Progress? Yeah. Would you object to having your prints on sale in Woolworths or Maceys?

EC: that’s the risk of an artist, the responsibility of an artist, not to reach up to that level.

JC: What down?

EC: Yes.

KR: When you were young you lived on a farm. When you till the earth you discover all the thngs that have gone before, things are thrown up – bits of bone, pottery – looking at these paintings the skulls seem to have been exhumed from the paint.

EC: No, just rather that skulls remind me of something very simple, one of the simplest things we know.

KR: As a symbol?

EC: Not just as a symbol but as a real thing. If you tough your head you feel the skull, not in a negative or macabre sense. In a lively sense – because the last year I’ve seen so many bright and cheerful paintings, but they were so dead. In painting you can paint a skull and make something more lively. Much of modern art is full of this macabre sense even if they are bright and full of colours. All modern art is full of death.

JC: But would you like to see your work as uplifting, inspirational to the audience?

EC: Yes.

JC: Do you feel your work is from a common sensibility, that you are working from common knowledge?

EC: Yes, it is concerned with one or two very simple things.

KR: Is it taken for granted then that there is a universal spirit?

EC: Not quite universal but a spirit is a sort of selection made by one people and one place / country.

KR: So, your spirit can be more concentrated if its more selective?

EC: Yes, if you think of Italian classical art – traditional art – Masaccio, Giotto, Piera della Francesca – these have been selected in a very small place, uch a small country, and not in the rest of the world – even if the world now speaks of it.

JC: Is that just to do with privilege?

EC: No, because every country selected something very eclectic in a certain way, it was the Italian selection that was best.

JC: Was that the first biennale?

EC: That was the real possible biennale, real possible selection. It’s not like now, when they make the biennale through intellectual choices. Because intellectuals dwell only on ideas, not on ral things – on qualities of feelings, of people.

JC: do you like the idea that your work might be misinterpreted?

EC: It’s not a real problem. I have great confidence that my work will survive if necessary.

JC: It’s not a problem how people interpret the work?

EC: That would be just taking on some more problems.

JC: Because you have no control over that?

EC: The artist can’t work on mass media.

KR: But then is it again an advantage being in Italy where – say at the opera – you get an immediate reaction to good or bad performances – a different immediate reaction to what’s going on?

EC: No, I’m not so much interested in the audience reaction, any audience is alive. I just live in Italy because I can manage to work there, only there, no here else.

KR: In Ancona?

EC: Yes.

JC: Apparently in Bologna there are all these arches and wonderful ruined architecture everywhere and young people dress up in Armani suits and pose around, yet completely ignore their background, ignore their history – there seems to be a visual contradiction – does your work deal with that, is it an interest?

EC: I don’t understand the young, but, actually, I don’t even understand why they are going on restoring old architecture. My idea would be to leave Venice, for instance, to fall down completely into the water – rather than restore it.

KR: The problem is people think they are recreating their history, think it is the same as the original.

EC: Yes, but one thing is restoration and one thing completely different, is the memory.

KR: People feel that if they recreate the physicality of it they will feel the spiritual element and they don’t actually connect back to the spirit which made the building or the façade.

EC: Yes, what would be important now would be the emotion and the feeling of seeing Venice crashing down into the water – that would be the only alive spirit about Venice. Because what’s important about Venice is the historical memory of what it was.

KR: When I was in Florence in February, they were restoring the Giottos and Masaccios.

EC: It’s terrible. That’s very American and Japanese.

It’s these cultures that think they can buy culture, just buy it.

EC: What a wonderful performance it would be, coming into Venice and see it crashing down.

JC: So when people try to remember and get it wrong, they create something new?

EC: Yes, but you can only remember when the thing is not there.

KR: It also means that the thing that goes on at the present isn’t valued at the present – there’s a continual looking back.

EC: The idea of restoration is the worst feeling this century.

KR: How would you feel if in 30 or 40 years time someone was to try and restore your paintings?

EC: That would be silly.

KR: Here we can’t even look at at some paintings because the light level is so low – you can’t physically se them – and it’s because they want to make them last.

EC: That’s all dead.

KR: Like mummifying?

EC: Yes, like a mummy. And when a new art magazine was born a few weeks ago, I wanted to dedicate it to Hugo Koblet, a cycling champion – a Swiss man because the magazine was Swiss – and that is an example of memory, of real remembering, something incredible and incredible character, personality, even if he’s dead or …

JC: From popular culture?

EC: Yes, it’s popular but also popular culture has its own real talent.

KR: Is it possible for an artist to become part of that really popular culture without compromising?

EC: Well, compromise has nothing to do with popular culture, but rather with elitist culture, so there’s no compromise you have to make to come in touch. ….(?) …. always compromise with their good taste or refinement, that’s the worst kind of compromise.

KR: If I could ask you about the paintings here now, were they conceived as a group?

EC: All the paintings I make are always born as a family and are all born together. I never paint on ne painting, always in a group.

KR: So how do you feel when the family go to rest somewhere else?

JC: Childcare?

EC: That’s no problem because I don’t know anything else of myself.

JC: And then you try to remember what you’ve done and do something else? You try to remebr what that painting was about and do another one and that goes on and on …

KR: The last painting here, ‘Transport of Rome : Horse, Camels, Statues and Lions’, has echoes for me of Kounellis.

EC: It can also remind you of Goya, of the Roman caves.

KR: The scale is so huge and the way the paint is used to physically create the people seen from above …

EC: If you look at Kounellis’s work it can remind you of all the popular Greek ….

KR: I’ve always had this feeling from those huge amphitheatres in Greece and southern France, that you are aware of that it all comes from Greece – that as you say in the poem in the catalogue, that it is the cradle.

EC: It’s like one cradle. The Mediterranean cradle. If you think of Delacroix, he doesn’t do anything new, but he just has this great energy of rare invention.

KR: But the story becomes revitalised with each new person telling it.

EC: Yes, the tradition has made everything, and every painter has to keep this tradition live.

KR: And the titles are part of the work, become part of the work?

EC: Yes, but each painting may have more than one title.

KR: At the same time?

EC: Or it can change while I’m working.

KR: and so yiu still work on the floor?

EC: I am always painting the same painting, only sometimes I do it on the floor, sometimes on the wall.

KR: So, the technique isn’t important?

EC: No.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The tape is turned off. We continue talking. Somehow, I recount a story I have just read in the paper about salmon, on hatching, only have to taste the water at that moment and their fate is sealed. Their destiny forever is to return to that water every year, seeking the same taste …. Enzo Cucchi wants the tape returned and restarted again.

EC: The tuna is called a noble fish, and he passes every year in the same period in the same part of the world. Even if he goes all around the world – every year in the part of the world that is the same.

The Story of the Tuna

There was a tuna once who was very young and his grandfather told him ’Remember, you are a noble fish’. At the time it was a mystery to the small fish, he didn’t understand what it meant. At a certain time in his life he decided not to go together with his group but to go alone in his experiences, to go alone around the world. And he had a bad time of being alone, so he decided to go back to his group and to repeat the same ways, the same moves the group made. And he felt so good, he could then understand that being a noble fish means.

I’d like you to start the interview with this story.

JC: We’ll probably get it wrong but we’ll make it up.

THE STORY OF THE NOBLE TUNA STARTS THE INTERVIEW