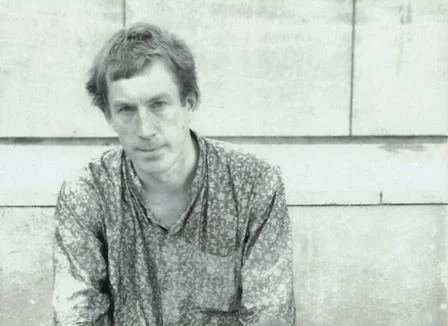

Jon Wozencroft Interview 1997

Jon Wozencroft

The 2005 interview edited by Jon Wozencroft 2026 for this web site.

A part of this interview was published in German p237/p238 in Neue Medien 2000

Published by Deutsche Verlags-Ansalt Stuttgart Munchen 2000

Digital Being

Interview 18th March 1997: Jon Wozencroft / Kay Roberts

(from questions given by Heide Baumann as part of her RCA/LCC Thesis)

Jon Wozencroft: The first point to be made which worries many of us, is that we are living through a critical transition which is far more incisive in the way we think and perceive the world, than anything that has happened in history. Unlike, say, the Gutenberg invention, unlike the splitting of the atom, unlike the explosion of the first atomic bomb in Hiroshima, there is no clear point at which this has happened and we can call “the start of it all”. The convergence of a number of scientific discoveries, consumer innovations, political changes, social developments, have been dovetailed onto us in the 1980s, to facilitate a fundamental changeover from analogue to digital.

The first perception one might have of digital is simply a change of format. One minute we are buying vinyl records and VHS tapes, the next we are buying CDs. Alternatively in text, one moment you are reading a book, the next you are reading from a screen. Or in the larger sense, the idea could be that it is just another improvement in the long line of technical innovations that we have based our civilisation on since the Industrial Revolution. The first thing I have to say about the digital code, which is easier to picture in terms of sound rather than anything else – although it applies to images and everything else as well – is the translation from sending information based on wave forms and vibrations to sending them in bits. No longer is the sound graph made up of curves, it is made up of jig-jagged straight lines, pixels. The way of looking at it, in typography, is to see ‘O’ drawn by hand, as it’s carved by a stone mason, as it’s cut by a hot metal letterpress worker; the ‘O’ then turned into an optical illusion, as it is based on a series of right angles. So it’s a trompe l’oeil based on resolution, the amount of pixels you can pack into a representation, to make the eye think it’s actually seeing a curve, whereas in reality it is a series of right angles and straight lines. The jagged edge.

Number two: the basis of digital technology stretches back centuries to the universals made by Leibnitz. We could take this as a starting point. You could say the straight lines of Roman roads. On the other hand you could look at the Difference Engine created by Babbage in the 19th century, looking at it in terms of algebra. Perhaps best, look at it in terms of processing, the innovations that were made in cracking the German enigma code at Bletchley Park by Alan Turing, Tommy Flowers and others. They worked through the idea of computable numbers, on number crunching systems, set up to go through the reams and reams of permutations that the Enigma machines were built to encode – based on the fact the Enigma had a series of rotors – I think they used 3 from a set of 5. Each of which had 26 permutations taken from the alphabet and ten plugboards that each used 2 letters. Thus 158,962,555,217,826,360,000 different settings (I looked it up). The mind boggles. So, to crack the codes, Turing’s team created the first so-called digital computer in 1943/44 called The Colossus – because that was exactly what it was, huge. And we can follow the development of the computer to IBM’s strategies in the 1950s and 60s, that harnessed this for business and military use. IBM computers would take up rooms of space and processing power, and today we land with personal computers that we freely use in the home.

The next point about digital is its role as a solution to the problem of storage. The need for more information storage, more being written, more stuff being produced as human culture and mass media communication expanded. The amount of people in the world, there has to be some way of taking a quart-sized piece of information and placing it into a smaller and smaller cup until it becomes a thimble and then a chip.

Kay Roberts: For me, this thing about reality and virtual reality is a huge problem, because reality is unquantifiable, whereas virtual reality is quantifiable, in a sense. Replying to this first question about a culture of simulation, are we being driven to a culture of simulation? I don’t feel that is what this is about, perhaps it’s a simulation of experience, but it’s not a simulation of reality.

JW: I think it’s the wrong word. I think a better way of looking at that is through the word ‘substitution’. Cybersex, for example, is not just simulation it is substitution and it points to a drastic conclusion. Can we still talk about being a sovereign body, in the way that you can have a consensus of reality, based on structures of human form, the family, parliament, legislation, society, culture, sexuality. Even if we are about to stratify in terms of high and low, upper class, middle class, and all of that, then what we now have is a new kind of stereo. And so people become more schizophrenic and for the disenfranchised (those not in the elite of the tech world) what one thinks of as the private self and one’s public face is more pronounced than ever. Between who you think you are, how you think you should be, what you want to be. Then there’s the question of surveillance, the ‘electronic eye’.

I think we ought to go back a bit in this first question, because the problems of reality do come back to that pure demonstration of how mass media can be used, as it was in the 30s. Of course, there are all kinds of collusions and conditions going on there as well, it is not all down to Hitler. But now there is the concept not of cold war but Virilio’s pure war, always war.

KR: I think it is down to trigger reactions as well. As I’ve mentioned I went to Nuremberg to try to understand how the rallies worked, as a physical entity, as an architectural entity, how you entered the space, how things were manipulated in what they did, in how people reacted. So, a lot of problems with virtual reality are that people behave like Pavlov’s dogs, they are not able to resist.

JW: Mankind has never been able to resist. There is a deep need that we have for spectacle, immersion, losing ourselves, whether in pagan rituals and May Day orgies, or whatever it was at Nuremberg. It does take place on a sexual and sensual level, our need for touch as an experience. The real question behind this is Motive, if you are going to act as a black magician, which undoubtably Hitler was, beholden to the occult, using Son and Lumiere spectacularly, in order to drive the German Nation to a frenzy of nationalism. Well yes, that’s cataclysmic. But if you have a Son and Lumiere concert, say Jean-Michel Jarre in the centre of Paris on a Saturday night, you can’t say Jean-Michel is a Nazi. But the tricks are basically the same.

The motive that comes into the picture with virtual reality is that we are not being given virtual reality to enhance our lives. We are being given virtual reality because people think they can make a huge profit on the back of it and sell more technology, plus keep people indoors. Also, in terms of my first point to do with digital media, the motive is another kind of storage. Virtual reality is a brilliant way of keeping people off the streets, blissed out and happy. That is what so much digital media is about. It’s a response to the storage crisis in terms of human information, but it is also a response to a human crisis in terms of over population. There are too many people and what they desire to have and to possess, with ease of delivery. To return to an earlier Marxist phrase ‘The Lumpen Proletariat’, it’s going back centuries. The difference with present technology its scale and intensity, and the sensual and psychic attack involved in it is much more acute. If you resist, you get called a Luddite! The Luddites were misrepresented by history but that’s another story. To be anti-digital is almost like being anti-water.

KR: Do you think it necessarily means one is a cynical person to be an informed observer of these events? It is always interesting to observe, to be removed, a way of observing as an outsider, to observe this phenomenon as people who are interested but not hooked into it.

JW: One should always try to be an actively-involved observer if you have the freedom to be so. The trouble with this side of it is that there are different levels of ignorance. There is ignorance in the sense of really not having the means, the privilege nor the education to absorb all these changes and to understand what is going on because of the pressure of life. And the second more endemic of the two is blind ignorance. People who realise what is going on, but who are complacent about it, who think it just takes too much effort to get their head around it, that it is too ‘boring’ and ‘heavy’. Of course it’s heavy, it’s not as if we are talking about the new Spice Girls’ album. With this particular question about the cynical and disparate living, there’s this post-modern syndrome with people living on their edge, who live in somewhere like Chelsea.

The next question… It seems to be straight out of the post-modernist world. We know we live in is total media, but we always have lived in a mediated world. The marathon runners in Greece, that’s media in a sense. The message that you run 200 miles to deliver… That is media/communication in its earlier sense. Bread and circuses at the Colosseum in Rome. Letter writing and the postal service before national newspapers came in the late 1900s… I could go on.

KR: I don’t see the difference in this statement of Nicholas Negroponte about computing not being about computers anymore, well that is because it is just media – it can’t only be about computing otherwise it wouldn’t be about anything. I don’t think it’s an effecting factor in the state of society.

JW: The whole thing about Negroponte is that his book is called ‘Being Digital’. That’s a contradiction in terms. It’s like saying ‘Being Robot’. It has little to do with human rhythm at all and that is the basic lesson of the whole set-up. Digital is a post-industrial phenomenon, not a human choice. Same old same old, efficiency and progress!

KR: And what about the ‘The Gutenberg Coming of Age’?

JW: That’s a catch phrase by McLuhan. My present understanding of the Gutenberg Galaxy is to do with the balance between what McLuhan termed ‘hot’ media and ‘cold’ media, and the print media and radio media, i.e. the hot media being a catalyst of different perceptions. The thing about McLuhan is he came out with a few brilliant observations, but his remarks were like grapeshot. One sentence would really be on the mark, the next complete bullshit. It’s very wild and unedited. But the internet is ‘cold and hot media’ at the same time, yet it has no acoustic quality, it is a dead zone of sound, compressed music and digital alerts. But it make you want to be – online.

KR: I also think there is a problem of people wanting to read into things that are historical… About a state at one time and transposing it into another time. Then reading into it what you want. That is one thing I feel about ‘culture’. You can’t in fact form culture, or there would be no purpose in going through it. Culture is something you can’t manipulate; it happens only in the future. If I honestly thought the ’hot’ one in the art world at the moment, who think they can manipulate culture, will be there in the future. I’m quite amused because exactly the same thing happened in the sixties. Everyone thought they themselves were wonderful and then they disappeared. In a way you can’t bank on where you will be in the culture and that’s a great thing.

JW: You can do your best using PR and marketing, but that’s not really what the public holds as its true feelings. Opinion polls should never be taken at face value.

What we can start to do is get a handle on new media, how new media has facilitated the conquest of space. Not outer space in the sense of NASA and the American moon landings, but space in the sense of mental space, our two feet on the ground, our immediate environment and homes. I think the next thing is the industrialisation of time. We are going increasingly into world time, the globalisation of time. We are going 24/7 and into endlessness. It’s about the standardisation of local differences. I mean this thing about ‘act local, think global’, it’s a very nice idea but well... Go down to your local newsagent and buy a local newspaper but ‘think global’. I can know a bit about what’s going on in Albania or China, I can read about it in the Guardian and think about it but how do I relate to it? What am I going to do which is going to change the situation? I suppose, be aware of it, simply.

KR: There is also an assumption that situations in any place in the world are also the same. I am often struck when I listen to a radio play where the action is historic, but the speech and action are all about the 1990s. There is no feeling for different places, different times and situations. There is no acknowledgement that we live in one rhythm and another person has a different rhythm. The meshing that Virilio speaks about is very perceptive about these problems. The falsehood of thinking you know what is going on.

JW: That brings us to another feature of digital. One of the aspects of the technology is the way it fundamentally enhances, sophisticates, explodes and embellishes the functions of television. It can hide its viral nature behind the cosy idea that it is all based on the same TV screen format that we are familiar with. That everyone is used to: the old glass teat analogy. Television, as we are aware, is not just to do with entertainment and rarely to do with emancipation… Rarely to do with knowledge or understanding the world, rare voices like David Attenborough and the dying breed of investigative documentaries are the exception. It has more to do with perception control, giving the edited picture and a false simplicity to complex situations. It brings us other considerations. The consensual hallucination that you live through in television – soap operas, news reports, all kinds of drama programmes – where you think you are in the heart of a community, or whatever, while setting up the new promise of cyberspace.

Cyberspace is in effect a new form of perspective. It demands a completely new perceptual outlook to understand what is being created. The idea that you have, at the moment, is that cyberspace is a zone where you can kind of wallow, engage in a lot of these pursuits of fantasy, to change your identity. The whole notion of cyberspace, in Greek, comes from ‘cyber’, to ‘steer’… navigation, and with that, danger ahead. About being in control of how you move yourself through a domain or a network, but this is not always the case. You already know when you try and go on the net to search links to the other places, you are navigating various sites, while hoping the machine will follow your instructions and do what you want, without a pop-up catapulting you somewhere you have no interest in. Or the computer simply crashes because it can’t keep up with your keystrokes. ‘Crash’ is an interesting choice of word. We should say ‘Fail’. Steering becomes about trusting the machine, not the hand that guides.

As Viriliio has pointed out, cyberspace is playing with the idea of Godliness. The idea you can transform these different realities – in effect, to be all seeing and to be everywhere. You can be all seeing and tap into all data/information, it’s there but is it trustworthy and accurate? The other thing about this God function is the way cyberspace already uses so many metaphors that are linked to fake heaven, some kind of astral journey. It’s very strange.

KR: I think that’s because in a lot of areas, people look for quasi spirituality – like a certain kind of music, perhaps it just shows you where the computer is in their lives and work.

JW: This is based on a series of inversions. One of the other dramatic things I’ve found with the idea of cyberspace, is that you are led to believe it’s about discovery, ‘interactivity’, ‘immersion’, the great words of the moment. There is a fine essay by Susan Sontag from the early 60s about Levi-Strauss’s Tristes Tropiques, which is about post-frontierism in anthropology. Not in terms of the conquest of land, but about mental states, regarding the emergence of counter culture and particularly this idea which we’ve grown up with – yours and my generation – that you find consciousness in unconsciousness. Find the jewels in the gutter. An old idea in art and it has a lot of truth in it. As a personal quest and made into a generalised pursuit, with an industrial and commercial underpinning, how do you combat the ‘triste’ that comes from all the realisation that the world is shrinking and your ‘discovery’ is making it shrink?

KR: Perhaps this is because it’s not an additive process. When you are looking round at information in general and absorbing it, building up the ideas inside you, it is an additive process. I don’t think it is additive when you get information on the net. Each thing stays its separate self, even though theoretically you can draw lines between it and interconnect.

JW: I think it’s definitely true that the more available things become the less absorbed they are. I think if you go into any shop in the country and buy your Oasis CD, compared to having to hunt out that really valuable item, you absorb it completely differently. Same with films, or any other ideas. We seem to have passed the stage when everything is about the pursuit of ideas and the development of ideas. Because of digital transition this is changing, so that everything is about the pursuit of form and the ability to change form. This is connected to the word ‘liquidity’. The whole approach to morphing, the ability to modify your body with surgery and prosthetics etc. To take it from another perspective, it's kids’ plasticine. All we are doing half the time is messing about with things because they can be messed about with.

KR: In fact, it’s immoral to be moral?

JW: Exactly.

KR: So where does this lead you? – If to question any sense of deep morality is not possible. If you just have to ‘let go’, to enter another reality, to find this other part of yourself, which the centre of yourself says is wrong or even damaging, or however it may be termed. That somehow you are uptight if you don’t enter this scene.

JW: It is scary because it exposes you, not simply to yourself but to generalised judgement. Any moral statement opens you up to personal attack, as I found myself. We’re not talking about religion, that’s another subject. But the thing that is more obvious and serious about morality is the whole sense of not even wanting to go there. Self censorship. These masks which we now have and like to wear, it’s not directly connected to digital cyberspace, but it is in a way, which is to also to do with the current resurgence of new age therapies. A particular attempt to California-ise, in terms of one’s desire to find your inner self. This can be linked to visiting cool restaurants and having raw greens or organic salmon, or whatever it is to do right, to make you feel you are changing things. It is a good step from fast food, but how much does it make a difference to the bigger picture?

Take yoga. Take the challenge of aligning a yogic perspective to an inner city existence. This is part of the stereo I was talking about. I’m not saying yoga is bad – it’s a fine discipline – but we shouldn’t kid ourselves that we are in the Himalayas. The whole travel aspect of this is very important because we are led to believe there are these devices or therapies that we can take off the shelf to improve ourselves. The wonders of mind over matter. It quite often works but if we are trying to say to ourselves that we have an understanding, equivalent of someone who has been brought up in a different tradition and who has it as a second nature, then we may be fooling ourselves. We might teach people about what living in urban space is about. You see the exporting of western urban experience into the Third World and see how it damages the social fabric of these places, especially in Africa and Asia. To think it doesn’t work in reverse is stupid and of course, it does.

KR: How do you mean?

JW: By virtue of the fact that there are powerful elements of magic generated by Eastern philosophers, that we can ingest without pause, because we can’t understand their power and use of techniques that have been refined over centuries.

I’ll offer an example. Chinese medicine. I’ve got a problem, I can’t get an appointment on the NHS. Am feeling run down. I’ll go and get some Chinese medicine. So, you’ve got the essence of whatever it is, you drink it and then, the next thing you know it you are eating conventional Western food, whether you are vegetarian or not. And so the whole thing is a total pick and mix. Multicultural sampling. At the same time, we are telling ourselves, we are wholesome, and in tune. Well, to be honest, to be in tune with Western society maybe involves a certain level of toxicity. It could be homeopathic to involve a certain (limited) level of toxicity in everyday life in order to survive it. In the way that getting your hands dirty as a child helps build your immunity.

KR: That’s like Guattari, he got an octopus which was in its own Mediterranean water, he put it into clear water and it died. He wanted to show you have your own environment, and you are related to that.

Jon Wozencroft and Kay Roberts look at the next question from Heide Baumann’s list.

Can we still trust our sight?

JW: Manipulated images? Well, the church was manipulating images centuries before Photoshop ever occurred to any of us, with powerful effects. So, again this is nothing new. Propagandists and political ‘neer do wells’ have been doing the same thing ever since. The problem with this question is that, deep down, we quite like the idea and we’ve grown up with it as an everyday. Powerful iconic images really do have a strong effect. For example, that posed picture of Elvis Presley, bending his knee with an acoustic guitar, and his curled lips, in the late 50s and 60s, it was a powerful thing to see this image as a young person. It was powerful to see picture of Brigitte Bardot in the early 60s. And Bob Dylan. Very powerful to see picture of fans mobbing the beautiful Beatles. Very powerful to see pictures and the film of Kennedy being shot. Images go right into your brain and into your heart. David Bowie. Etc. etc. We like the idea that we can get close to the action, have proximity. It’s about sensation and truth.

KR: I suppose what this is touching on is the way you can make something look like it happened, and it didn’t. In much the same way Stalin used photographs, and got rid of people.

JW: Do you remember the obsession at the turn of the century with spiritualism? People who produced photographs with fairies in them and it was all fakery. People accepted that because it was a nice idea to think about magic phenomena going on. The 19th century had been so stratified and controlled in terms of morality and behaviour. This is another question which touches on aspects of public image and private belief and behaviour. The Victorian era wasn’t sexless, not at all!

KR: I also think it’s about whether people are curious and if they are a thinking person or not. If you see something that is in front of you, you usually question it.

JW: You should, but you often don’t.

KR: That certain people don’t question has always been the case. In the same way that people saw mediaeval painting and thought there were angels, it’s just one cultural rule asserting its strength. To them it was real. If you didn’t think it was real you’d be excommunicated.

JW: My point about this… the genie is already long out of the bottle. We were talking about Leni Riefenstahl’s camera angles in her early 30s films. With regard to the integrity of the image, we might be able to save lots of people from being duped. At the moment you could say that the mass acceptance of digital manipulated images can be turned, therefore the mass acceptance that the camera usually lies would be a good thing. A positive step forward – maybe. Utopian? Probably.

KR: I suppose if you start out believing nothing is real, and therefore nothing being ‘true’, you start thinking about what is true and what is not.

JW: What would be really nice is if we were really going to look into the effects of digital manipulation. What would be great is to get a wedding photographer to take a series of wedding photographs, and then digitally manipulate them, and give them back to their clients with their new partners, to see what they make of that.

KR: So: can we still trust our sight?

JW: Yes, of course we can. We just have to learn what the vocabulary is, what the language is. We have to become aware of motive and technique. There is a very acute proposition made by Virilio in one of his recent texts, where he says what we really want is to go blind.

KR: Because?

JW: Because – Overload.

Because the hyperactivity, the over stimulation of the optical sense, the auditory, the tactile, the olfactory, the tasteful, leading is to a situation where we say “For God’s sake just switch it off”. Leave me out of it. Baudrillard said similar things about hyperreality.

KR: I went to quite a stimulating lecture last week, about light. It was given by a physicist, but it was quite a lot of philosophy from Plato on, what he – Arthur Zajonc – was saying was, you see by ‘luxe’, by God’s light. But you don’t actually see with this, what you actually see with is your inner light. Without the two you don’t see anything.

People who are born blind and then have their sight restored, have to touch an object, then they ‘see’ it. It is within you that the sight comes, not from without you. Understanding comes from within you. All that light is doing is making it possible for you to discern.

JW: Beautiful. Another important thing is the difference between a life which is commanded by natural light, and a life which is commanded by projected light, television light, computer-screen light. And the way that these lights, in fact, are going deep into the human psyche. These lights might all be replacements for the moon. These televisions, these computers, might all be replacements for a primal contact we need to have with the moon and the stars. We are part of a cosmic spirit, that we have lost in this century.

KR: Well, looking into a warm fire …

JW: Yes, the same. Ancestral. The light, the glow and the movement.

KR: The fantasy would you enter. The thing the computer does, is not allowing you to enter your own individual world, it’s giving you its fantasy.

JW: Not only that, if you just take it in a completely physiological point of view, what the television screen is doing is from the cathode ray tube, same as the computer screen, is it is projecting 25,000 volts of light at you. You wouldn’t stick your hand in an electricity socket. It’s the motor, it’s thrust at you, you have no guard rail. This is going back to the Virilio quote, you have no protection against it. You can shut your eyes and not watch it, but if you are exposed to it, there is no filter, so close your eyes.

KR: So maybe the problem is, rather than trusting our sight, that maybe we have too much to see.

JW: Absolutely. There is too much. If you think of it in terms of food – We can just gorge and go completely crazy with it, and then we can go bulimic, or retreat to live in the country. Food is one letter away from flood. There is a big thing that, when you go out of London or any big city, you don’t have the same media saturation, you are in quietude, but I don’t think that’s true. It’s still connected to loneliness, isolation and the need for engagement. You might need to watch Coronation Street even more!

KR: There is this question, which is about cyber worlds being in their infancy.

JW: There are two things about that. Cyberspace will always be in its infancy. It is about the infant state… The next stage that is just around the corner. This is one of the things about digital technology, is that having crossed that rubicon, digital technology can be effortlessly, infinitely and progressively sophisticated. So there is no comfort zone, or salient, ambient period, where you can get to grips with one particular set of devices before the next ones are impelled at you. The whole landscape has changed. If you look at this in terms of the net, one year everyone is fixated with HTML, then with VRML, then needing to get up to date with JAVA, and then the next thing is going to come along, shock wave or whatever, it’s a very short cycle.

As a consequence, it promotes an infantile attitude to content, because everyone is so set upon what’s next in terms of what it should look like. It creates, as we see coming over from America, this expression ‘dumbing down’, of people who should be, by now, grown-ups. Again, toys for the boys, unfortunately it’s very difficult in this context to go into a very different subject of gender and sexuality, and feminist ideas. It’s a whole other discussion. It’s difficult to see how women would do it any differently, because the tools, and the whole construction of the beast is anti-human rhythm, anti-intuitive, anti-soft. The great claims made for non-linearity and chance advances, in terms of intuitive information, seems far in the distance whatever Apple might introduce.

KR: So, the last question, what about current developments in living in the information age?

JW: It’s about everything to do with the feeling of being human. Is mainly about the idea of new technology, no, it’s about our survival as individual, sovereign, thinking beings. Are we living in an information age? Yes. Everyone has lived in an information age. The information age when scribes had to sit down and copy manuscripts, illuminate thought for hours and hours under candlelight. As far as they were concerned it was the information age, and it’s a conceit that we think that ours is the first. So I also want to say, I’m not against having a computer, I want to simply suggest that very little is appreciated at this point as to what we have got ourselves into.

KR: It’s just what information is imported to the age. The information we want now is so banal, the quality of information, that’s the question for me.

JW: It goes through a chain, doesn’t it, or rather a spiral? You start with data. You make data information, the information starts to be crafted or designed into what we call knowledge, and the knowledge has to link up finally with understanding. If you go through that whole path, great, but it stops before things mature to the knowledge stage. It’s as though there is a shutter that comes down and the information being this dull, dry stuff, that has to be jazzed up with graphics, PR fluff and dramatization etc. It creates the zombie culture.

KR: I think what is meant by information here is almost like facts. Perhaps you could say it is a data age. For me it’s not an information age, because it’s a misinformation age. As every age has been.

JW: there is:

data + design = information

information + teaching + experience = knowledge

knowledge + self-awareness = understanding

‘Information’ might point to a limited view of the world. ‘Communication’ began with its meaning concerning transport, the railways, connecting people over distance. It didn’t refer to media. There is hope. Not in terms of not being aware of what’s going on, but the steps that need to be taken in terms of consciousness. The human condition is undergoing quite a challenge. Who the hell knows what will happen next? Between what we collectively want, and what we will be made to do and be governed by.

JW: Postscript.

This interview with Kay and Heide we did 28 years ago, since when it has laid dormant. In October 2025 I edited it for clarity and accuracy (it was us talking, not a text for publication), fluidity (grammar) and repetition, otherwise it is as it is. Much has happened since. Thanks to Dave Barnard for making the reconnection.