Interview with Oladele Ajioye Bamgboye 2000

Written for Revelation but not published

With Kay Roberts 30th October 2000

KR: When I looked at the Intelligence show and saw the ‘Spells for Beginner’ – that’s quite an old piece – 1994 but I hadn’t seen our work before. What I was fascinated with is something which is probably tangential – like the fact it is quite personal, within the photographs there are quite a few fabrics, a lot in fact, and then the multi-use of your body – as ghosts at places you’ve been, plus the still photography and film. I then read the Writings on Technology and Culture book and in the end went to see Voila. So, what I think would be interesting for the magazine is to set the scene of the work and that you perhaps go through the transition from the work that you were doing – at I’m not sure, but I presume, that is from when you left college.

OAB: Not really because the only time – well – probably to begin, as you said, my background is a little bit tangential, although to return to that with new technology now it is quite interesting to me because things I wanted to do 10 years ago are now possible for me. I don’t have to hide the fact that I was an engineer before, didn’t study art theory, even though something like that really is academic and then I eventually went to art school and I went to The Slade.

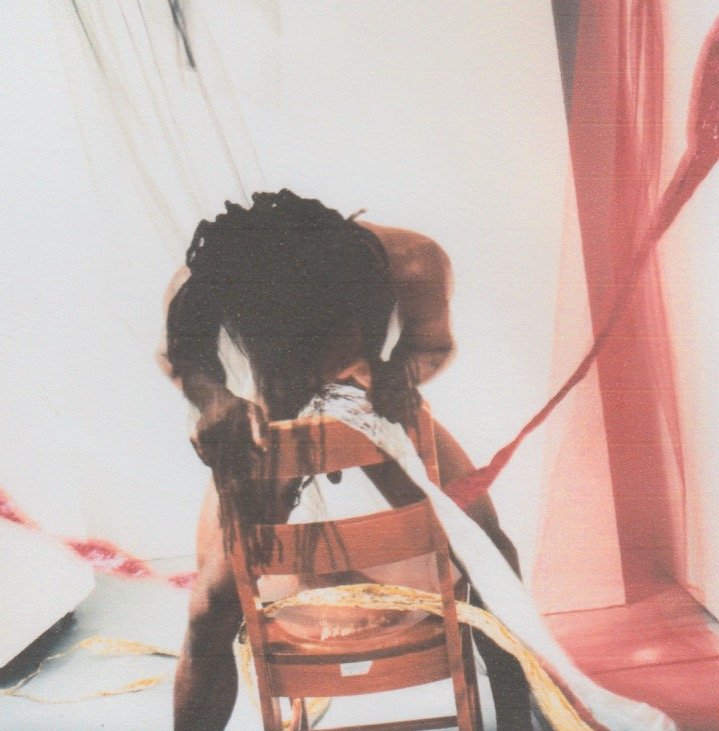

Oladele Ajioye Bamboye 1994

KR: When were you at The Slade?

OAB: 1996-98 – did a Masters degree there and that was the only time I studies art.

KR: That was with Stuart Brisley?

OAB: And Michael Newman. Stuart left and Michael began, I was quite glad to have caught both of them. That was a moment.

KR: Well, Michael is so theoretical – that must have been quite a change for you.

OAB: Yes, it was, because on the one hand I guess that before that I had been practising art for 10 years,.

KR: Doing?

OAB: Doing photography, video, bits of performance. I started doing photography because after I graduated as an engineer I looked at it and thought ‘mmm – no thank you’. Very nice to have that rounding and I was much more interested in the thought processes I had. So I thought – better take this – and in fact the curse was called ‘process engineering’ so that was quite interesting, processes and how one could engineer processes and I think tht becomes more relevant to me now in terms of project management …….. one can employ as an artist, it is much more fragmented now. So when I finished that (Engineering Degree) I decided that I wanted to do art but then so for me to do something like photography, it was immediately something personal and not like engineering – it was the opposite. Then I started by doing photographs of performance.

KR: Of your own work?

OAB: No, Performance of artists at Transmissions Gallery – I tried to build up the archive for them. Because they didn’t have any photographic archives and I could take pictures and I thought – you know – so I did that. It put me in touch with a lot of artists.

KR: With people like Christine Borland?

OAB: Well, people like Christine Borland and Douglas Gordon, at the time I was starting to show photography they were just about doing the same, because they are 2 years younger than I was. So it is quite interesting they are kind of my contemporaries. It’s quite funny, you know, and I remember at the time if you were showing photography it was very difficult in Glasgow. In fact at the time I ended up helping to start the Glasgow Photography Group which became Street Level and was one of the founders of that., so I was quite active in that. As a result I started to make a lot of exhibitions and gradually – and for me it was quite interesting because I was immediately drawn to the interior. Something you have commented on – people were interested in the performance art, the qualities of that and the power of the image.

So I always knew that in England there was a black arts movement and it seemed a strange luxury to have, if I can out it that way. Because when I came down I was unclassifiable, it was strange for me – because I had no relation with them like the one I’d had with Douglas Gordon and Transmission Gallery. To be abstracted into a black – that’s bad – and I think that informed a lot in my early works. They were largely autobiographical, really about making sense or making sense of where I was and using the medium very experimentally to subvert or to really to suppose the fragmentation of our thoughts was around. Then I became quickly interested in European painting, portraits and so on, but I could never stand the sculpture, maybe because I wasn’t good at it, in place of constructing – because the fact things were photographic one tended to use photography to subvert that.

I liked stained glass – there was this thing of looking through something that was transparent and because it is transparent, the reflection, you can look back at you nd so on, different layers.

KR: Because some of the things, kind of, just to hear you talking, remind me of Dan Graham’s rooms, where you get this multi faceting. It is the same kind of thing – that mirroring. Back and forth between different layers of reality.

OAB: Yes. Well at the last Documenta 1997 Dan Graham had this wonderful piece there, I spent most time in there, it was great. Here you have another artist looking at …. I wouldn’t say I could make that work but I got a feeling for it. I also like the videos Bill Viola quite a lot because of the spiritual depth that they have which I think is quite bold.

KR: I think it looks a lot simpler than it is. It is technically very sophisticated, and it has again tht magical leap into another dimension.

OAB: On reading your article a few days ago, on trying to find sense of place within technology, and within what I would say also that sort of performance life- for me eventually I was photographing performances, the photographs I take were quite staged – may be installations. I made bit of films for a start, and then videos. When an audience looks at a video of a real performance …. especially if there is a chance to play around essential dislocation, I feel very strongly that in the actual material of the work.

KR: One of the things Margaret Wertheim talks about in her chapters is that we have a sense of the virtual now because of television – that it is not a bold concept, for me looking at your work, It’s also to do with this thing called ‘the other’ – the viewer can’t escape from that.

OAB: They are implicated in the work – I think I like to make things where you have to make a judgement on it somehow – that’s not such a heavy thing but it’s like you know, I think even though sometimes a lot of newer work is where the technology thing is interesting for me because I can then impart a feeling of involved and personal detachment that happens afterwards. For me it is like coming in a dark room and so on, you switch a light on, if you’ve been travelling for example, you comeback form holiday, it’s dark – maybe you’ve been in a warm climate or where it’s a bit bright and it’s winter – like January – when you come back – it’s dark outside and you put on the light (an so on) – the glow of the bulb is so light and something happens afterwards because you switch it off, but it switches off you can see – it’s a wonderful sense when you can see the glow of the bulb dying away – that sort of thing. If I could make an artwork like that, it is really wonderful, because I think within that, all the complexities of ‘the other’ – the relationships, between ourselves in different places. Or the fact we know now, that even though maybe it becomes more interesting for someone like me that, on the one hand, one feels like something like geographies and, yu cannot make sense of places any more, but I’m not sure if in any sense whether I was interested in places before anyway, because the works are in the main, within them, are for me done for something just in between those places – that were perhaps half fantasy, the things themselves were very real, but it was arrangements like as the miss-match of fabrics and the texture, were the things that were quite sensational, that gave you he boundaries to approach the work.

KR: Well, I think I prefer the one with the tartan to the ones with the corn.

OAB: The one with the corn is a bit more symbolic, can be read as being more symbolic in many senses, and it becomes a sense of feeling naturally. The figure in that piece is perhaps the closest I think I’ve come to a portrait, there is that.

KR: I read about the fabric in your book. How does this word ‘exoticism’ fit within that context? Can technology get rid of cultural and economic difference?

OAB: Not really. It can emphasise it some ways – that is actually what it does. I’ve also heard other the other thing where globalised theories, the geographical school of thought which says ‘well yes, there is the notion of periphery now, it is so two things can happen’ – either of the peripheries are so important that the centre ceases to be so central, ot that the centre is so fragmented that the relationship between the centre and the periphery is different. But I think what happens is that now we can see more things, there are a lot of really clever things with fragmented centres and then shift them round. The relationship between periphery and the centre can be very constant all the time, for me, as an artist it is very interesting, I have a project coming up now ‘On Masking 3D” which I’m going to do a Dutch residency. It is based on the Benin Head.

KR: When I saw your work at ‘Voila’ the Benin Head was one text that came up.

OAB: I am quite interested in this – you know this year is all about the Queen Mother. She is 100 and the quintessential mother figure, so it is amazing for me, the amazing relationship between the Queen Mother and this Benin Head which is in Liverpool – and partly owned by the Queen as well – and the King of Benin. It is very interesting because I dreamed of this idea and contacted them with the idea ……. 2000, you have one already – and the relationship between, for example, is that obviously, it is there, but it is interesting to look at the different ways people could have access to this head. I said ‘ I know there are certain problems you have with this head, it is not just enough to have it on the web site for people to look at. It would be interesting if people could actually possess a head, take it away’. What it is means is that people from Benin could look at it.

KR: Why did they have problems showing it?

OAB: Well, the thing is, on the one hand the history of this head, obviously – there are some sites and there is one site in Britain which has been active, especially by the late Bernie Grant, for returning everything, especially this head, and they can’t do it.

I am mostly involved in a project later this month called ‘In Discipline’ in Brussels at the Palais de Beaux Arts, in which I am going to talk about some of those things. What I am doing there is I am actually be going to be in discussion with John Picton from …….. Arts. He is an authority on Benin heads and a bit of a radical and is there is a break between him and another expert (whose name escapes me now). What is happening now, is, there is a counter shift, there was an article in an ethnological magazine saying ‘ don’t return this head, only can be old to private collectors in the West. I know what I’m talking about because I am an authority in the West’. John definitely doesn’t agree, so I’ve asked him to deliver a lecture as part of my project. Then within that, to move the project on, to actually place this head, or a digital form of it, within cultural architectural landscapes, landscapes of memories that people make within communities everywhere. Develop certain technical things somehow. Ways of interacting with the head which are collective of whatever your thoughts are, feelings, touch, and so on. That is the culmination of all the things I’ve been doing – from the personal, autobiographical, reflections made on yourself and how you defined within what you physically look like i.e., the pictures, moving to how you are defined by texts or reactions. That is what I learned to do at The Slade, where I would have to learn about all those classical, continental things, things which probably I didn’t want to learn so much about, but I didn’t want to go to a place where I was repeating. Now I feel a bit more balance because I can finally make real sense of European concepts of art. Moving on to the newer projects.

KR: The one I saw in ‘Voila’ was very interesting – I’ve not seen that kind of artistic analysis of how we archive mentally – the concept of the show was very interesting. Your work is described in quite practical terms. You weren’t controlling the way it printed, it was random but the content wasn’t random.

OAB: Not really. It was quite structurally controlled within the program which generated texts, and when I looked at it, I thought ‘well no’ it was quite interesting but too structurally mirrored, which | didn’t want, and this became a philosophical battler of syntaxes. What was very interesting for me was to take texts which already existed, which I had, and those texts were from various exhibitions, which I was sent. A lot of them were from the ‘Africa, Art of a Continent’ exhibition. I am not particularly interested with the objects but the texts, which are so visual and so overpowering in so many ways. I made another project which was just the texts, this was my degree show at The Slade. Just the texts on the wall. Very small, very minimal – and what happened with that was – I was quite interested in looking, for example, now you don’t have a description of this (a painting on my wall) but supposing you have description for this here and then you moved house, then that was then removed and all the unsaid things and all the relationships that were formed were there.

KR: What about other artists’ work? For example do like, say, Sophie Calle? It’s nor about culture …. What would be the difference?

OAB: I think her work is also about culture because I think it is very difficult to take an object and divorce it from its cultural context. Also, it is interesting to me to see when in one case a work is more cultural than another. I try to resist that. Because by taking things that are applicable to engineering, for instance, a laser printer, you can be exposed to the mechanism but it doesn’t matter any way. With the assumptions that are made within those texts of situations that are not subjected, scientific or rational analysis, but have a huge weight in not only a cultural sense but also in a sense of colouring and building a picture. I was very interested in the textures of the work printed, then when you then put it differently, to compare different styles of writing and collections and from that angle. Using the fact it was an object was a trap for people to look at the thing, I thought, rightly or wrongly, that people would be interested in a head. Then when the thing was really printed a little bit haphazardly, but not too much, it became much more for me, about erasing the sense through overload of text. So when you look at at it, a lot in it became much more like a stamp, which is interesting, but it is even more interesting what happens when something is written onto a computer hard disk, which is wiped a few times, the retrieval from the memory, subjected to fluctuation of the network – the time and so on – which that programme is. Then delivered, because it can never deliver very accurately, but at the same time, the structure is not totally random. It was incidental and immediate, like a throw away thing, almost. It had therefore, the weight of a leaflet, a flier, but it was more than that.

KR: Have you consciously chosen not to use your own body in the recent work?

OAB: It’s a good question.

KR: Or is it something that’s happened?

OAB: It is something that’s happened but at the same time, the thing that changed this ios quite dramatic. I guess in many ways what I’m trying to say, is to deal with the mind. Within those transitions you can see certain photographs. I have a lot of photographs still which haven’t been shown and have that transition between having long and short hair.

KR: I was going to mention that – did you notice a difference in how people reacted to you?

OAB: Yes, because some people think you are not as attractive or sexy as you were. That is interesting because that is probably why bone does it. It is directly related to what happens when a woman at around 30 decides to dye her short hair, or to dye you hair. Those sorts of things are interesting but for me in particularly interesting in that this sort of change, which is just a change in appearance, because there is this weight of the hair – it has a lot of associations and all that ort of stuff – after a while you realise – yeah, but it was a phase, you grow – not that you grow out of it, but you realise the pressures and expectations of that put on you, do not interest you any more. So you get rid of that, or you transform yourself and immediately there is a sort of intellectual implication to that, very, very strongly. So, for me it was very interesting to, from this thing, to be very, very smart.

KR: So, an external judgement is made?

OAB: Yes. I am. Still fascinated by this quite a lot. It is very interesting, obviously one could delve into it quite a lot. So a lot of these series of pictures which I made, I have short hair. Some of them have been exhibited alongside but not. Really. The connection between them was so strong – I thought ‘I can’t handle that, it’s too much’ before it was hard enough to try and say a lot with the fact the body is there, it has a certain physical attribute, but actually it is always quite fragmented in different spaces, and that really keeps it almost as a motif in many ways. It was quite difficult in one sense to equate to um – to put it shortly, I thought at one point, would it be an interesting thing to do some similar picture tht had colour in them, with short hair. I thought – no not really – then I thought it becomes interesting to me to rationalise, to make sense, of mental challenges, that you feel much more now.

What becomes more interesting – when you talk about ‘exotic’ – when something happens that is separate from the self, and external, one can say that it is exotic by definition. But when it becomes a serious label of exoticism, when perhaps one puts cultural things in the photograph, I think it is quite difficult no matter how much the artist intends. For example, the picture we are looking at now, ‘The Lighthouse’, people are going to see the black body with the girl in the middle. It is a racial thing people out in, of course it’s there. It is full of a lot of provocations in the picture, in fact it is all provocations. Until we eventually reach the fact we have been provoked by this thing but it exists as a separate entity in itself, and that is the whole point of it. Lightness is quite important, in that, there is humour there.

KR: One of yoga teachers said ‘If you want to get enlightenment get light’. A different form of light but lighten up.

OAB: I remember this – I can’t agree more. I hope that within what I am trying to do, I guess yiuy could get this kind of enlightenment – lightness.

KR: Like the light bulb you were talking about earlier, so that the enlightenment stays there?

OAB: Even not to give the work away when you’ve made it, that’s the transgression between something that’s crafted and really not so much an idea, but it is not so much about that. There is nothing you can do about that because the context and the time. That explains why the timing of the showing of the video piece at the Tate, because I thought, now we see these sort of things in dramas, like ER and so on – now mixed relationships are not so …… there are still certain things about them in some sense but within that piece there are certain audiences who will go in, will perhaps go in there, who look at a setting and look at the elements of taste for example. I wanted them to go in and say ‘where do these sofas come from?. They go in there and say ‘; Oh they are from Habitat – that’s interesting’. And then you look at the video and think ‘Oh My God”.

KR: Well mixed-race relationship is common in society but when it is personally happening to you, it is very different. It is a dilemma. There is this schism, it is taken as fine by society, but when it happens to you, it brings you up against yourself.

OAB: Exactly. It was very, very distant. Well, that was deliberate – I must admit, I do do that. It is interesting because I guess I don’t really believer in the power of art works to really assimilate life. It is plain up to a point one can only play these games with the structure of what is in front of you. There are some pieces which are just too personal.

KR: Do you think that in time that might change? You know Ian Hamilton Finlay said every artist should have a hole that they put works into and bury.

OAB: Well, I’ve got a few holes, you are going have to wait. Because I know what ever I like to put out, there are challenging in many ways, because people come up to me and say ‘ what on earth is that’ – it is very fascinating to get an interaction with people, this is really great, very fascinating, because people get very moved by things, they say ‘I don’t like that, I liked the way it was, it is too distant, too cold, I’d like something more warm’. When it was in Kassel, the exhibition, there certain people came up to me and said they didn’t like the way it looked at Africa as a sort of intellectual construct. Really it was not, it was showing African scenes and so on, but it was quite detached. They thought this was a chance to show a little bit of life – these people who lived there – well really that’s because I only lived there for ten years. That’s how African I am, That’s my whole point. These things are very interesting for me to look at. I can say when I make pieces of work it is designed to answer each sense or structure.

The one thing I think is very interesting now, is that almost every show - I don’t make many shows here.

KR: I’ve noticed that – why do you think that is, choice or what?

OAB: I think it is the form of my work. I do more things in Germany.

KR: Well, that is understandable – there is a whole genre there. Do you know thw ork of lother Baumgarten?

OAB: Yes, I know this. It is very fascinating, the work in Kassel, some people in Holland took that for a Baumgarten work – I thought , what a compliment. Some people were very shocked by that, so called African peers, - well you should be insulted.

KR: There was a show at the National Portrait Gallery of people who are more at home in other places than their home country (1986). His work is very romantic, everything has a this beauty about it – it is the antithesis to your work.

OAB: Yes but is interesting this connection because we all know what happens with contemporary African art nowadays – it’s promotional. On the one hand I have been told that part of the problem with my work is that the form of it is dispersed and that it sort of existed in different forms, not only in forms, but in terms of the intellectual forms of it. Perhaps one can be very interested in stuff about place, where there is a sense of place very strong in it, but what happens when that is taken away – then you have really abstract pure forms. You say that – how you can actually move through space – in an abstract sense – that is the culture, never mind who they are, in a very digital form. I am very interested in that. I am not sure how far this can go. I also like a Bernard Cohen’s brothers things. Aaron was a successful painter for many years, left in the 60’s, moved to California and studied programming for 25 years. He built this machine that paints. It is fascinating stuff. I came cross it about a year ago at The Slade. For me it is interesting when not only the hand of the maker is involved, how do you impart culture on to it, when we remove that completely and put it into code.

Why shouldn’t you call that contemporary African art as well?

KR: Again, it is the same problem as in anthropology. What do you do when a tribe discovers fridges and electricity – do you hold them back and say ‘you are quaint, you are great, you are alright like that because I want to look at you like that’. I remember having this conversation with Baumgarten, about my sadness that the native people he was working with in Brazil were going to get perverted by western values and that their simple life would change. And he said ’Well if you were them wouldn’t you want electricity, warmth and so on’. This was not what I wanted to hear – but it is the same thing, it is the same thing as saying ‘this is African art and that is how it stays, it is not going to shift into the 21st century’.

OAB: Exactly and I would even say more – instead of giving them fridges give them CFC free technology. But you are not going to give them that because they might even go beyond you, because they have that extra that you do not have. You are a bit afraid they can handle what you can handle and still have a bit of air.